Social anxiety is defined as a “marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which someone might be exposed to possible scrutiny from others” (DSM-5, 2013).

In other words, this type of anxiety is caused by social situations and the fear of being negatively judged by others.

Examples of situations that might cause anxiety include social interactions such as having a conversation with someone or meeting new people; being observed, such as when eating or drinking in public; or performing in front of people, for instance giving a speech or a presentation. The situations that cause anxiety can be different for different people. For example, some socially anxious people feel okay talking to people they know well but worry about meeting strangers; for others it is the other way around.

If you suffer from social anxiety, you will likely worry that you might act or show anxiety symptoms that will be judged negatively, in other words that you will humiliate or embarrass yourself, or be rejected, or offend others.

You will perhaps avoid the situations that trigger your symptoms, or else you endure them with intense fear or anxiety, sometimes developing ways of coping known as “safety behaviours” that you hope will make you feel more confident, such as not looking people in the eye so as not to draw attention to yourself; sitting on the outside of a group; using alcohol or drugs and so on.

Social anxiety can negatively affect studies, work, friendships and romantic relationships and it can also get in the way of everyday functioning such as making telephone calls, interacting with people in shops, buying clothes, having a haircut and so on.

In other words, if you experience social anxiety, you fear that others will think badly of you, and you often believe you are not as good as other people. This makes social situations very difficult, or impossible, with anxiety affecting the body, thoughts and behaviour.

If you suffer from social anxiety, you might notice the following reactions in your body, mind, emotions and behaviour, before, during or after social situations:

Body sensations (fight or flight response)

a) heart racing or pounding

b) tight, painful chest

c) tingling or numbness in fingers and toes

d) stomach churning or butterflies

e) dry mouth

f) an urge for the toilet

g) feeling jumpy or restless

h) tense muscles

i) sweating

j) breathing changes

k) dizziness or feeling lightheaded

l) blushing.

Thoughts/feelings

a) a strong sense of fear that is over-the-top but that won’t go away

b) worry that you might act in a way that will be embarrassing in front of others

c) believing that others are judging you or thinking badly of you

d) telling yourself you must look anxious

e) thinking you will make a fool or yourself or look stupid

f) believing if you are nervous people won’t like you or will think you are stupid

g) wondering if you are “boring” or “strange”

h) picturing yourself in a negative way, which is how you fear others see you, such as flustered, weak, timid etc

i) before an event, anticipating that things will go badly

j) afterwards, repeatedly imagining that you looked stupid or behaved badly.

In other words, a lot of your attention becomes focused on yourself and how you are coming across, which paradoxically can increase your anxiety and interfere with paying attention to others, making conversation even harder than it was already. In addition, repeated (negative) post-event evaluation can lead to feelings of shame or humiliation, which are unpleasant and can add to problems with self-esteem, making it more likely that you see yourself as “a failure” and feel anxious next time you have to go somewhere.

Behaviour

a) avoiding difficult social situations

b) avoiding talking on the telephone

c) doing things to try and relax in social situations (“safety behaviours”), for instance drinking too much alcohol, smoking more than usual, rehearsing what to say in advance, offering to help so that you keep busy, sitting in the corner, planning your exit, visiting the toilet frequently, avoiding eye contact, or talking too much or too little.

Unfortunately, many of these actions are unhelpful for a number of reasons:

1) They might cause feared symptoms – for example, trying to keep track of what you have said and what you are going to say next, can make you more (not less) likely to stumble over your words and lose your place in the conversation.

2) Other people might also notice these actions, including you not attending social events or withdrawing in the moment, not making eye contact, sitting hunched over and so on, which unfortunately could make you appear unfriendly, distracted or disinterested.

3) Safety behaviours may even draw attention to you, and/or to the very behaviours you are trying to hide. For example, if you speak quietly, others may have to lean closer to hear you, which increases their focus on you and probably your fears about what they are thinking of you.

4) Safety behaviours stop you learning that you do have the confidence and ability to deal with social situations. Although they are used to feel better in the short-term, they can actually keep the problem going in the longer term!

Who does it affect?

Social anxiety disorder is one of the most common forms of anxiety. In any 12-month period, it affects around 2.3% of people in Europe (DSM-5, 2013) and 7% in America (DSM-5, 2013). Over a lifetime, 12-14% of people experience social anxiety. Prevalence decreases with age, meaning it occurs more frequently in younger adults (18 – 29 years old) than older ones. Generally, it is more common in females than males and the gender difference is more pronounced in adolescents and young adults. (DSM-5, 2013).

What causes it?

Most social anxiety begins in adolescence, with onset often between age 13 – 15. The causes are not completely understood. However, multiple interacting pathways might be involved. These include:

1) Genetic transmission (in other words it can be inherited).

2) Seeing your parents show fear and avoidance in social situations plus an overprotective parenting style have been identified as important in some studies.

3) Both 1) and 2) might help explain why social anxiety sometimes seems to run in families.

4) Biological factors – as a species, we have learned to fear and avoid angry people/expressions.

5) Environmental factors – distressing, stressful or traumatic events in early life (such as being bullied or abused, being regularly criticised, being embarrassed in public or your mind going blank during a performance) are often reported by people with social anxiety.

6) Social anxiety disorder can also be related to “low self-esteem” or a poor opinion of self, which may begin in childhood or adolescence.

7) Some people may be more naturally anxious or have learned to worry about social situations.

8) Some psychological models stress the importance of thoughts in the causation/maintenance of social anxiety, as discussed above, including negative predictions about future social events, negative interpretation of performance in social situations, focussing attention on oneself, and repeatedly ruminating after an event on how it went.

9) Avoidance and/or safety behaviours also serve to help maintain social anxiety.

Social anxiety can occur alongside other mental health problems such as depression or generalised anxiety. In addition, people with autistic spectrum disorder or ADHD sometimes experience social anxiety. Social anxiety can be a risk factor for alcohol abuse.

How can I help myself?

here are a number of ways to overcome social anxiety. These include:

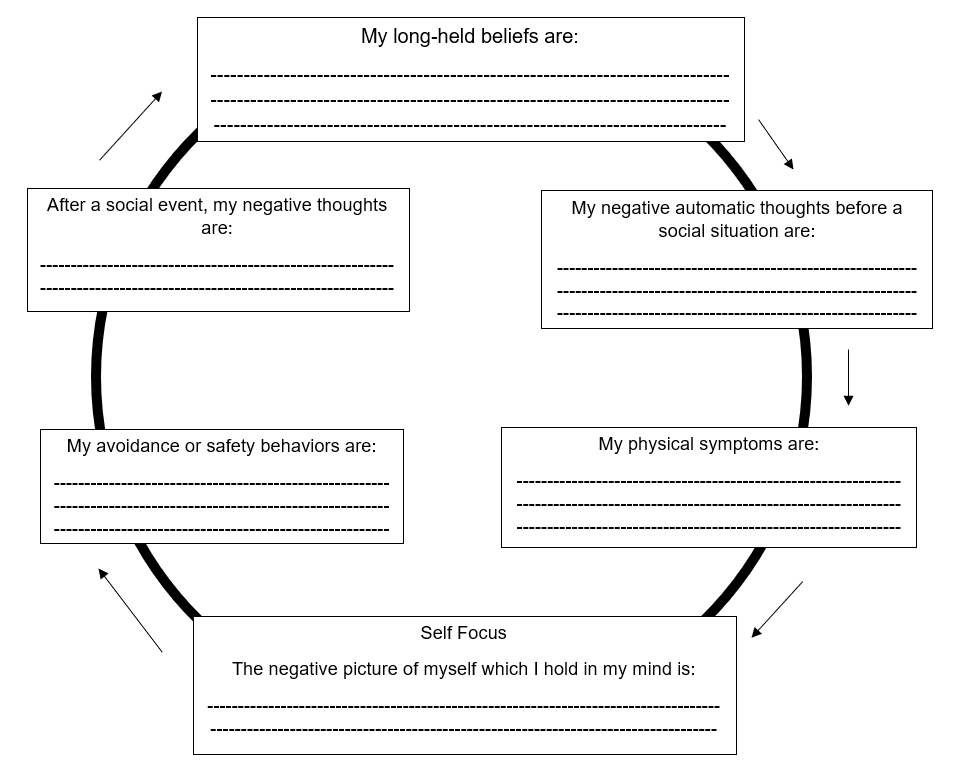

1) Understanding social anxiety, such as by using the below worksheet to help identify your thoughts, physical symptoms, behaviours and feelings in a particular social situation:

2) Understanding and reducing negative thoughts, beliefs and images. This can be done in a variety of ways, but the aim is to gain distance from your thoughts, seeing them as mental events, or opinions, rather than facts. Just because you think others are judging you negatively, doesn’t mean they are! Some more information/worksheets to help this process can be found here:

3)

Reducing how much you focus on yourself. Learn to pay attention to what is going on around you, using all your senses. Question if you are as much the focus of everyone’s attention as you believe you are – watch them and see what you notice. You can also practise mindfulness techniques, bringing the focus of your attention deliberately and non-judgementally to something in the present, such as your breath or an activity. This handout has some more information/ideas about mindfulness:

https://www.getselfhelp.co.uk/docs/Mindfulness.pdf

4) Becoming more comfortable with uncertainty. 100% certainty may be desirable, especially if you are anxious, but it is not possible. Try acting “as if” you are happy with uncertainty, such as being more spontaneous and not over-planning.

5)

Tackling avoidance and safety behaviours. This is probably the most useful way to help overcome social anxiety. Begin by making a list of all the things you avoid and the safety behaviours you use. Then try gradually facing your fears, in order from easiest to hardest, slowly introducing healthy coping strategies and reducing and dropping unwanted habits. It is important to stick with the anxiety until it reduces, which it will. This worksheet might help:

https://www.get.gg/docs/Avoidance.pdfIf it helps, you could treat each change you make as an experiment, identifying your predictions about it in advance and then seeing if they come true, to help decide if the new behaviour is something you wish to keep practising.

6) Tackling the physical symptoms of social anxiety. You can learn to recognise the early signs of tension and prevent anxiety becoming too severe, such as by learning to relax. This can be done through exercise, music, reading, watching television or practising relaxation exercises, yoga or soothing rhythm breathing (see link below):

What if I need more help?

Cognitive behaviour therapy is recommended as the best treatment for social anxiety. You can access this through your GP, who can also recommend medication if this might be helpful. Alternatively, you may wish to consider therapy with an AnonyMind clinician. Please contact us if you would like to hear how we can help.